In Part I of Improve Your Cycling, I focused on how to smooth out your pedaling to make you a smoother rider, a faster rider, and a more efficient rider. These are things triathletes should be focusing on all the time, ways to save energy AND go faster. In Part II I want to address the last three things in my list of poor cycling habits, and here they are as a reminder:

In Part I of Improve Your Cycling, I focused on how to smooth out your pedaling to make you a smoother rider, a faster rider, and a more efficient rider. These are things triathletes should be focusing on all the time, ways to save energy AND go faster. In Part II I want to address the last three things in my list of poor cycling habits, and here they are as a reminder:

- Pedaling that’s not very smooth, covered in Part I

- Too much movement of the upper body while pedaling

- Poor gear changes, not in time to match the changes in course and terrain

- Pedaling in the wrong gear

As I previously stated, these last three poor habits not only slow down the rider but they can also have a ripple effect on the following riders, when the bike in front of them suddenly slows down or shifts around unexpectedly and they have to move to avoid them. When you’re riding in a pack you want to ride smoothly and predictably, ready for anything that happens to the riders in front of you, and be ready for the terrain ahead.

Efficient cycling is about applying power to the pedals in a smooth fashion, our upper bodies should remain “quiet” and relaxed, not locked onto the handlebars. Excess body movements and hanging on too tightly to the bars results in that motion being translated to the bike, the front of the bike weaving back and forth, so learn to relax your shoulders and focus on pedaling smoothly. That covers the second item in the list, while the last two have a lot in common.

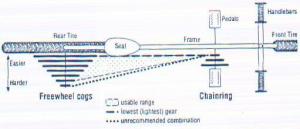

Triathletes that come from a bike racing/training background, and maybe us older cyclists that learned to ride with only 5, 6, or 7 gears to choose from in the back, seem to be more aware of what gear they’re in and “where” the next gear they should use is to maintain their momentum. I wonder if newer riders don’t just pick a chain ring (the gears up front, the little ring for going slower and uphill, the big ring for going faster), and run through the 10-11 gears in the back, before finally switching to the other ring, without thinking anything about their cadence dropping too low, spinning too high, etc.

The roadie culture is to educate young and new riders on how to ride and act in the peloton, letting them know right away if their actions are dangerous towards the other riders. The safety of the entire group depends on each and every rider’s ability to ride aware and to be conscious of everything that is going on around them. Many triathletes don’t get this kind of pack education and some respond negatively to it when they’re told how they need to ride within the group, which is a shame because ultimately their own safety depends on it and they could find themselves shunned by the group.

To confuse you and to try and explain what I mean by your “next” gear, I’ll introduce the term gear inches to your vocabulary, as I never hear this term used anymore, I think it’s become somewhat anachronistic. A gear inch defines how many inches your bike will move forward with one complete revolution of the pedal for a given size wheel (in this case 700c, the standard road bike size), for each different gear combination.

The following is an example of what a typical gear inch chart would have been with a five speed freewheel and a 42/52 set of chain rings, compared to today’s bike with an 11 speed cassette and a 39/53 set of chain rings.

- The numbers down the left are the number of teeth in the freewheel/cassette; the more teeth you have the slower you go.

- The number in the chart in parenthesis is the sequential order of the gears, starting with (1) as the lowest.

- (L) and (H) indicate a chain ring as Low for the little ring or High for the big ring, to indicate a particular gear combo, e.g., “I was riding in H6 to get ready for the sprint.”

- The larger the number in the chart the faster you can go.

- The “next” gear is the one that has the smallest difference in gear inches.

|

Gear Inch Charts |

||||||

|

5 Speed Freewheel |

11 Speed Cassette |

|||||

|

Little Ring |

Big Ring |

Little Ring |

Big Ring |

|||

|

42 (L) |

52 (H) |

39 (L) |

53 (H) |

|||

|

14 |

81.0 (7) |

100.3 (9) |

12 |

87.8 (-) |

119.3 (16) |

|

|

17 |

66.7 (6T) |

82.6 (8) |

13 |

81.0 (-) |

110.1 (15) |

|

|

21 |

54.0 (4) |

66.9 (6T) |

14 |

75.2 (11T) |

102.2 (14) |

|

|

24 |

47.3 (2) |

58.5 (5) |

15 |

70.2 (10) |

95.4 (13) |

|

|

28 |

40.0 (1) |

49.5 (3) |

16 |

65.8 (8) |

84.2 (12) |

|

|

17 |

61.9 (6T) |

75.3 (11T) |

||||

|

19 |

55.4 (5) |

68.1 (9) |

||||

|

21 |

50.1 (4) |

65.1 (7) |

||||

|

23 |

45.8 (3) |

62.2 (6T) |

||||

|

25 |

42.1 (2) |

57.2 (-) |

||||

|

27 |

38.8 (1) |

52.7 (-) |

||||

Notes

- The guys in the bike shop would tell you that these days you shouldn’t be using the last two gears in the back in the little ring and the first two gears in the back in the big ring due to “chain cross”, which can cause premature wear on your chain, and these gears are indicated with a dash (-).

- You’ll see that for the 5-speed freewheel there’s a relative tie for 6th gear, so you effectively wound up with only 9 unique gear combinations, while for the 11-speed cassette you have ties for 6th and 11th place, minus the four gears you shouldn’t be using, you wind up with only 16 unique gears out of a possible 22 combinations.

- It’s not imperative that you follow the order of the gears exactly, just that you know that being in the other chain ring might be easier or better when you switch gears in the back. The smaller the gaps between gears (a smaller drop or gain in the gear inch numbers), the less affect a gear change has on your cadence, leading to a smoother pedaling style.

- First gear for both setups is about the same, 38.8” vs. 40.0”, while today’s rider has two “bigger” gears, a 110 and a 119 to use to go faster. An option for the faster “old” guys was to swap the 52 tooth chain ring out for a 54 to pick up more speed on the top end, which changed all the other ratios accordingly.

What I’m trying to convey here is that riders who grew up with the 5-6-7 speed freewheels had to do a lot of changing back and forth between the two chain rings to select the next gear on the list. Being in the correct gear to match your cadence and the terrain is the same as when you drive a car with a manual gearbox, which is also becoming somewhat anachronistic these days, where you change gears to keep the cars’ engine in powerband to extract the maximum amount of performance. Our own cadence while we ride is just like the powerband of a car, so you need to know what gear you’re currently in to know where the next gear is in the list and how to get to it.

If the gear inch conversation is too much for you, think about this as an example on todays bicycle. You turn off a road while riding in H4, your 53/21 combo and encounter a slight uphill and then a sharp uphill. You should know that you could shift into H3 and then L5 and then L4, etc., to keep your cadence up before you hit the hill and not when you’re already on the hill, which drops your cadence and kills your momentum.

Our old school rider would have to do another set of changes back and forth between the two chain rings to find himself in the correct gear and would have practiced doing this quickly and smoothly with one hand reaching down to their friction gear-shift levers on their down tubes. Todays’ riders push a lever or button without lifting their hands off the handlebars, and yet I see many of them (maybe you?) moving all over the place, the front of the bike swinging back and forth and wonder why?

A corollary to the previous comment is watching people allow their cadence to drop too low before switching into the next gear, as they start to grind and work harder, wasting energy and momentum again. As cyclists are approaching steeper sections of the road they seem to be hanging on to their smaller gears, saving them for when it gets really tough, which is actually making their legs more tired before they even reach the real hill, completely defeating the purpose of the gears.

If you’re beginning to grind on the shallower slopes of a hill you need to change gears to keep spinning as long as you can. Yes at some point we all just have to suck it up and push hard up the hill at a lower cadence, but don’t wait to switch to the smaller gears, use them to go as far as you can while holding a higher cadence, it will save your legs in the end.

Hopefully some (all?) of this has sunk in and you’re thinking about situations on your usual bike route where you feel like your pedaling isn’t matching the terrain and you’re losing time and wasting energy. If you think about what gear you’re in, i.e., which chain ring and what gear in the back, 1-11, and move to the next gear right before you need it versus after wards, then your pedaling form will remain strong and smooth, versus forced and choppy, and you’ll find yourself moving ahead with less effort and wasted energy.

In the end, understanding how the gears on your bicycle work, knowing what gear you’re riding in at all times (within a gear or two, here or there), will make you’re a smoother and better rider, one that is better adapted to riding in a group, and as a triathlete, one that is saving themselves from wasting energy that they’ll need on the run to follow. I think a little education can go a long way to making everyone better riders, so I hope you take the time to think about this on your next ride and hopefully you’ll be surprised on how easy it is and how much smoother the ride was.

Good luck and happy riding!